Cannery Row

Press

Where Words Defy the World

Issue 2

March 2021

Cannery Row Magazine

A Literary Journal . . . with Benefits

by Tanja Rabe

Editor's Desk

by Tom Leduc

Poetry & Musings

by Matthew Del Papa

Mat's Musings

by Katerina Fretwell

Poetry & Musings

by John Jantunen

Short Fiction

by Rebecca Kramer

Musical Interlude

by Rebecca Kramer

Creative Nonfiction

by Lee Tamahori

Screenshots

by John Jantunen

Editor's Desk

by Denis Stokes

Poetry & Musings

by Jacob Shulman

Short Fiction

by Matthew Del Papa

Short Fiction

by Cheryl Ruddock

Fishbone Gallery

by Nicholas Ruddock

Poetry & Musings

by Tanja Rabe

Creative Nonfiction

by John Jantunen

Book Nook

Born in Kingston - Made in Canada

What's in a Name?

by Tanja Rabe

_edited_edited.jpg)

Welcome to the second round of Cannery Row Magazine and our gratitude to all the creative folks featured in this edition.

Upon release of Issue 1 in January, the first comment we received on Social Media read as follows: "Funny to see a mag with a classical American name discussing this." (referring to an excerpt of John's Editorial Is This "Canadian Enough" For Ya?)

I was rather delighted that the inherent and, might I add, intentional irony of choosing this particular header for a Canadian publication had not gone unnoticed and, since the remark conveniently ignited the topic for this introduction and happened to coincide with a poetic theme on offer, I am thankful for the initiative.

Every artist struggles to varying degrees with christening their creations; at times pieces literally name themselves, some writers find inspiration after a good night's sleep, whilst others agonize endlessly over choosing a title that reflects their work's intent. Most of us, myself included, probably fall into the latter category as many ideas sound infinitely better in one's mind than on the page.

After careful consideration as to what we were hoping to achieve with a literary journal, the title question loomed. I had whittled it down to Buffalo Jump, a picturesque allusion to humanity's stampede towards its own demise, but its indigenous theme - though well intentioned - exposed us to potential backlash from the 'Cultural Appropriation Guard', our pasty complexions a dead giveaway.

As I glanced at our bookshelf awaiting divine intervention, my gaze kept returning to the short row of Steinbeck novels, dog eared and half-buried under a stack of contemporary Fictions. I reached for a small, well-worn volume often eclipsed by the author's better known works. Flipping to the first page of Cannery Row and drifting over the initial paragraphs, it quickly dawned on me that the passage, as if by design, perfectly underscored the purpose of our journal (view it on our Homepage).

After the first wave of excitement had worn off, we found ourselves facing the same dilemma - how to contend with its origin - when the solution emerged in a discussion that John would later frame into his first Editorial:

Where are our own celebrated Canadian authors and stories that illuminate this country's darker aspects, past and present, and confront their true legacy, in depth and without compromise?

Where are our voices of conscience represented and honoured in the media and on our bookshelves?

And forgive me if I shall remain unimpressed by any reference to our Literary Elite with its patronizing stranglehold on what constitutes appropriate fare for a sheltered readership, let alone its exclusionary cult of privilege and promotion of blissful ignorance that are furthering nothing but a decline in our communal intelligence.

Contrary to the popular but, in my opinion, misguided view that literature serves first and foremost as entertainment, the awe-some power of 'words on a page' has been amply evidenced since the dawn of civilization. Be it in encouraging public engagement to the extreme of revolution or inflaming prejudice and persecution through hateful propaganda, there's no denying its reach as a tool for conscientious social transformation or as a weapon of mass destruction. The silencing of dissent itself by banning 'subversive' works, committing them to the flames and exiling their authors to the cold dungeons of oblivion plainly manifests the fear that a determined pen on paper can instill in those who abuse positions of privilege and power.

Literature, in its myriad forms, has always been in essence about Learning, its entertaining aspect an integral part to keeping our minds engaged. Being truly human implies a continuous journey of gathering and sharing information and experiences in an exploration of ourselves and the world around us. It is at the point where we forsake this lifelong growth and curiosity to the sole pursuit of escapist make-believe that we have abandoned all desire for our continued existence and willingly fall prey to what we fear most.

As an antidote to this epidemic of apathy we had to reach across the border and enlist, posthumously, the help of an American author, namely John Steinbeck

His legendary classic The Grapes of Wrath demonstrated effectively the might of the pen wielded by a righteous mind in search of truth and justice. This powerful, courageous, deeply disturbing and thoroughly engaging portrayal of human suffering and inequality during the 1930's was instrumental in shaping public sentiment surrounding the devastating and far-reaching impacts resulting from The Great Depression. And despite initial backlash from several fronts, Steinbeck's books - amongst other critical classics - have remained and thrived on our shelves for close to a century now though sadly reminding us, as we look at our present situation, that real change can be illusive and requires constant vigilance.

We tend to arrogantly point a cautionary finger at the United States and its many crises, ever at the ready to deflect from our own deeply embedded issues, ignoring and even muzzling the warnings of whistle blowers here at home. As long as we can keep up appearances, keep the nation's skeletons buried under our rapidly shrinking icecaps and maintain the pretence of a national identity based, ironically and tragically, on not being like our neighbours to the South, all is well in Canlandia.

We need to wise up to the fact, and this 'virus' offers the perfect analogy, that we, like it or not, exist evermore in a global context, socially, environmentally and economically, where borders have always been rather ineffective constructs for keeping out the 'hordes'. The unwelcome truth that these 'hordes' have largely originated and flourished within our own borders since the genocidal inception of this country and their menace has long since breached the gates to all we profess to hold dear - at least in word, if not in deed - has been conveniently ignored, often outright denied. And to make matters worse, we foolishly consider it in bad taste to point out the crazed elephant stampeding through our streets, let alone put a resolute end to its rampage.

And as much as we relish our national pastime of condemning Americans as a whole for their 'outrageous' attitudes, its citizenry has one public attribute we often sorely lack in this country: the courage to stand up and the will to speak out, to take to the streets - or to the page for that matter - and engage in open, angry dissent despite the threat of reprisals. Free discourse, by definition, inevitably invites disagreement, if not outright confrontation, and the dangers of hateful speech are all-too-well illustrated throughout history. Yet that should never stop the conversation we, as Canadian citizens, need to engage in at all times - be it to continually challenge systemic inequalities and corruption or, ultimately, to fight for the survival of our species. And since great literature arises from conflict and crisis, it would certainly befit our country's literary community to truly engage the world around them beyond the veil of wishful thinking.

Thus it came to pass that we invited John Steinbeck, if not in person then at least in spirit, along on our literary journey as a challenge and inspiration to ourselves and all Canadian authors who still recognize and honor the ever-important role that true storytelling simply must continue to play in our lives.

Needless to say, as a small, online publication we might just as well join in with that ubiquitous homeless guy furiously venting his frustrations at unwitting passersby as he roams our streets, hoping in vain for a faint echo of our discontent to reverberate throughout the hallowed (or is it hollow?) halls of Canadian Literature.

Hope Springs Eternal, Tanja Rabe

Peeking Through The Fence

by Tom Leduc

America,

would you please clear out

your driveway, give up on

those old, rusted cars

and mind your grass.

I have an electric lawnmower

you can borrow.

I saw your wife the other day

forever in a swimsuit,

perfect, perky, plastic breasts

exercising but never fit,

tanning but never tanned,

swimming in shopping bags,

basking in name brands.

There I go again, assuming

everything of power is male,

who says America is a man?

Let me start again.

Peeking through the fence

I saw your husband

BBQing a steak, measuring

manhood with muscle and mustaches,

slugging back beers,

bragging to himself about

the time he did something.

_edited_edited.jpg)

I noticed your children also

the oldest with his golden smile

football star, womanizer

spitting image of his old man.

Not like the youngest.

No one ever talks about him

doing time, drug addict.

Too bad, I liked him,

funny kid with a big heart.

Speaking of kids, I spent

an hour at the fence

talking with your daughter.

Second year university

deep in love, so much potential

you should really pay

more attention to her.

Anyway, this is getting weird.

I’m spending too much time

watching you, obsessing really.

I must get back to cleaning up

my own house, lord knows

there are cobwebs to sweep.

But before I go

can you stop your dog

from crapping on my lawn

and trying to hump mine.

She’s fixed and will never

give consent.

Baby Elephant Rock by Robert Michelutti, Capreol

A Small Northern Town

by Mat Del Papa

Capreol is an odd little town. How many places can boast that their firehall and river both burned twice? How many are named for one man* but were in fact founded by someone** completely different? And how many can claim to have outwitted a vast multinational corporation - not just once, but several times? None, that’s how many.

There are other oddities about Capreol. For instance, the laws of physics don’t really seem to apply here. How else can you explain why it takes twenty minutes for a Capreolite to drive to Sudbury but over an hour for Sudburians to drive to Capreol. Maybe magic? That’s the only logical reason for how the City of Greater Sudbury made most of the town’s equipment disappear as soon as the ink on the amalgamation order had dried - only to have it all reappear in the City’s garages later that same day.

Strange occurrences are commonplace in Capreol. All of Northern Ontario has its quirks, but for some reason we have more than our fair share. Like the reverse vampires that make up the City of Sudbury’s police force. You haven’t noticed? Vampires, the regular kind, only come out at night. Reverse vampires only come out in the day. The police, what little presence we find in town, always seem to return to the City just as darkness falls. Maybe that’s just a coincidence, maybe not.

There are clones in our town too. You see them everywhere. The same few dozen people keep popping up all over the place, usually volunteering for some charity or another. They have to be clones because no normal person could be in as many spots as these few handfuls seem to be. ‘Course it could be something more ordinary, like teleportation or ghosts.

And, boy, does Capreol have its share of those! The Legion Hall has its ghost. So apparently does the old Capreol High School building - changing its name failed to exorcise the spirit. The town library is supposed to be inhabited by some otherworldly presence and I’ve heard tell that the railyard is haunted. That’s not accounting for some of the older homes. And then there’s the graveyard. I don’t even want to speculate on what sort of spectres, poltergeists and whatnot call that place home.

Oh, and rumours! Capreol has plenty of those, too. Small towns are notorious for the speed gossip; nothing travels as fast as a nice, juicy rumour or some vague innuendo. Some think that’s one of the downsides of small town life but I always figured, it just goes to show that people look out for each other. That’s another thing that more and more marks our town as different: people still care. Not as much as they used to maybe - the pace of modern life makes it hard - but some few keep managing to find the time.

So what does it all mean? Capreol is an enigma in many ways. Unique but still much like every other small town across the country. It has roughly three thousand residents but somehow many more call it home. We’re an out-of-the-way place - literally at the end of the road - and yet traffic passes through here nonstop, heading east and west on our century-old railroad.

The contradictions are almost endless. A quiet place that loves to party. A past that inspires fierce pride but is soured by a tinge of regret, and yet still harbours hope for the future. There is always something, some small sign, that reminds us Capreol is, and always will be, a great little town. Maybe more than a bit strange, but we wouldn’t want to change it even if we could.

* Frederick Chase Capreol

** Frank Dennie

Gratitude to 'The Capreol Express' for sharing Mat's Musings with us on a regular basis. To find out more about 'The Little Northern Town That Could' visit: mycapreol.com and enjoy its biweekly community newspaper.

Connections, Katerina Fretwell

_edited.jpg)

Destination Covid

by Katerina Fretwell

A snake-oil shill,

I belly up to global droplets,

my spikes shake with venomous glee

at the financially vulnerable:

poverty rising in Nigeria and the DRC,

packing the poor in shanties ripe for my spread,

many gasping on one mouldy mattress,

or dirt floor, begging for a breath –

helpless against my serpentine desire.

Or in the sub-Saharan civil wars, I feel the trembling

of a boy soldier forced to shoot his mother

and watch the leader rape his sister,

gunpoint enforces the pillage and plunder

of families in flight from rebels and rulers.

Masks and hand wipes a luxury, there's no time

to sanitize when life itself is at risk –

impotent against my serpentine desire.

Or in crowded communities and inner cities,

perfect breeding grounds in my viper-dens:

Canada's castoffs can't wash as needed in sick water;

can't stay six feet apart with twenty kin to one shack.

can't forego low pay at unwanted jobs, exposed

along with elders abed in filth: few staff, many beds –

hapless against my serpentine desire.

Or in smugglers' boats shilling their cargo,

terrorized refugees, into the camps

before the West's hostile shores can deport them,

their fear drawing in my forked tongue.

Like my greedy-gene ancestors:

plague, polio, smallpox, influenza ...

I set my shafts on defeated, defenceless humans,

simple as the rich shredding fair-rule parchment –

protected against my serpentine desire.

In Memory

José Saramago

Niche

by John Jantunen

The walls were amber, the colour of caution.

The contractor, upon entering the apartment for the first time, couldn’t help but take his steps slowly, advancing down the hall with the deliberation of a person approaching a busy intersection, though the vibrancy of the yellow on the walls here was dimmed by lack of an overhead light, the result of a long-dead bulb in the fixture which the apartment’s owner had never bothered to replace. In advance of the contractor’s arrival, the apartment’s owner had replaced all three of the bulbs in the living room’s fixture and even if he hadn’t, the bank of windows on the far wall released enough light into the room that one wouldn’t have noticed a marked difference in the colour’s heat at nine-thirty in the morning, the time the contractor had arranged to meet with the blind man.

After lingering a moment in the entranceway, the contractor suddenly accelerated, as if a traffic light had turned green, and strode towards the kitchen. The blind man waited until he’d made his appraisal and his footsteps were approaching him before remarking, It is all the same, It is bright, Yes, Yellow, Goldenrod, I see, Is it rude to ask why, No, Then why, When I was a child, you see, there was a sign outside my school and everyday I saw this sign flashing yellow, A yield sign, Yes, Children at play, that’s what it said, Everyday I saw this flashing yellow light on my way to school and now that I am old it is the only colour of which I have any memory at all. You could see a little then. Yes, it was hazy, a blur, like looking through frosted glass.

The suggestion came from my sister, the blind man explained while the contractor tapped on walls and made a few measurements.

It was, from the inflection in her tone, a sarcastic barb, an attack on him and his stubbornness. It’s a dump, she’d said the last time they’d spoken, you might as well be living in a prison cell. It suits me fine. And it smells. That is the woman across the hall, she has cats. Mother hated you living here. Mother no longer has much to say on the matter. That’s cold. She is dead, I can be as cold as I want. She left you a tidy sum. No more than she left you. She wanted you to use it to improve yourself. So like a mother. If you aren’t going to move, then the least you could do is fix the place up, A few pictures on the walls, a shelf, Perhaps a chandelier, That’s the spirit.

He’d drawn up the plans that same night.

I want to open the place up, this to the contractor while the blind man prepared coffee in the kitchen. You want more space. Yes, One big room, Yes, No walls at all, Just the four. No problem. When can you begin? Next week. That soon. We’ve had a cancellation. Perfect.

An active mind awakes early.

The blind man opened his eyes when the dawn was no closer than the dusk, his thoughts brimming with the sounds that had yet to fill his apartment. It was the day construction was to begin, although deconstruction might have been a better word except that it was a word that the blind man did not like. One should never deconstruct to find meaning, one should always build meaning from one’s experience, there is no other way, that is what the blind man argued when he discussed such matters with the people at the publishing house where he worked as a translator of books into Braille. Some of his fellow employees agreed and told him so, others did not and said nothing. Lying in bed, he wound through these conversations again, letting them blend and bleed into each other until his biological clock, a dull throb telling him that his bladder was full, forced him to seek out the bathroom.

The contractor came an hour later. The dishes from breakfast were drying in the rack and the blind man was pacing from room to room, running his fingers along the walls separating each and whispering, Goodbye my friends, goodbye.

The arrival of the contractor had an altogether adverse affect on the blind man, one that, if a pun can be forgiven, he had not foreseen, for there is a vast difference between thinking up plans in one’s head and having them come to fruition. In the space between the two, as narrow as the knock on the door and the first tentative strike of a sledgehammer on the wall between the kitchen and the living room, the blind man had a sudden attack of nerves. For those who have not experienced this feeling it is not unlike swallowing a piece of glass and waiting for it to tear into the lining of one’s stomach. It is as irrational as it is unpleasant so the blind man can be excused for taking leave of the contractor and fleeing his apartment. He crossed to the door of the only other apartment which shared the hallway with his, both of which he’d bought some years before when the market was low and the previous owner was in need of some quick money for reasons he didn’t mention. He knocked twice on the door, his hands still shaking from the attack, then inserted his key into the lock and turned the knob.

The smell of cats, urine on the carpet and excrement left too long in the litter box, settled around him inducing a sensation not unlike that of stepping into a sauna before one gets used to the heat. Hello. There was no response, the TV in the living room was too loud for the old woman to hear him. He stepped inside and closed the door and immediately felt a pressure on his leg, one of her cats coming to greet him. It rubbed against his shin and he bent to stroke its fur, for the most part matted and hard although there was a tuft of softness, untouched by the filth of its surroundings, under its chin. He ran his fingers through it, then stood and walked towards the sound of the voice coming from the television.

He rarely watched TV or, for that matter, seldom listened to the radio, preferring the texture of words and the noise of the city from his balcony (although he wasn’t averse to some quiet music before bed) and he felt no compulsion to listen to what the voice was saying, though he did note that it was speaking with an authority usually reserved for news announcers and politicians.

Hello, he said again when he was at the end of the hallway. He heard the familiar creak as she shifted in her chair. The voice on the television grew weak. Only when it was reduced to a slight murmur did the old woman speak. There’s something going on, Yes, You must have heard the noise. Sorry, I’m having work done in my apartment, It is very loud, I apologize. I have heard nothing, I mean there is something going on out there. Her hand motioned towards her balcony and, though the blind man couldn’t see the gesture, he understood nonetheless. They say it’s an epidemic. Her voice strained under the word like it was impossible what they were saying and she hadn’t yet decided whether she believed them or not. Recovering, she added, Of blindness.

She cast him a sideways glance, giving him a look identical to one a white man might give a black man if their conversation were to touch on slavery, but all the blind man knew of it was the silence that came after. In this pause he caught a few words and phrases emanating from the TV but not the glue holding them together so that they didn’t make any more sense to him than would the pieces of a picture puzzle jumbled up in a box.

Do you want me to tell you what I think? The old woman was talking again and it took him a moment to separate her voice from that of the man on the television. What’s that? I don’t think people are going blind, I think we are already blind, Blind but seeing, Blind people who can see, but do not see, What do you think? Perhaps. I suppose it won’t be so bad for you. No, I suppose not. And for me neither, I never go out. She stopped talking then, she had become distracted, maybe by something one of her cats had done, or maybe it was the news announcer or politician on the television crying out, I am blind, God help me, I am blind!

_edited.jpg)

When, early Tuesday morning, the blind man had welcomed the contractor and his assistant into his apartment for their second day of labour, there was nothing to suggest that the work would not progress, as work invariably does, whether it is translating a book into Braille or hammering nails, and as he had expected it to. Yet it would transpire that the work would hardly have begun when suddenly it would stop. This created no shortage of inconvenience for the blind man but it was a misfortune which he’d shortly reconcile himself to as, over the course of the following days, there would be ample evidence to suggest that the state of disrepair in his apartment was the least of his worries.

Feeling anxious from the constant barrage of hammering and the grate of machinery, he’d taken the phone onto his balcony and called the publishing house to enquire about a possible assignment. After navigating through the electronic answering service, he reached the editor in charge of Braille publications and listened to a message recorded the previous Friday which explained that the editor would be out all afternoon but that he would be back at his desk on Monday. The blind man left a message telling him why he was calling, nothing in his voice to suggest he thought it odd that the editor, who was a fastidious man not prone to oversights of the professional or personal kind, did not update his greeting, then hung up and dialed his sister. Likewise, he got her answering machine and he hung up before she’d advised him to say something after the beep. Unwilling to return to the noise in the next room, he sat down in the closest of the two chairs arranged in front of the balcony’s table.

His balcony, five paces wide and three deep, the solid edges of it hewn out of plaster, rough to the touch, overlooked an alleyway. Opposite, there was a row of apartment buildings, known to him through a description provided by his sister, and at either end of the alley there were streets that unto themselves were unremarkable except in that they led to a much larger and busier street. It was from this street that most of the sounds he heard while sitting on the balcony emanated, bouncing off the apartment buildings so that, by the time their reverberations reached him, they were more often than not unrecognizable. Sitting there, he would often close his eyes and pass the time speculating on the possible origins of these auditory signals, much the same, he thought with some satisfaction, as Plato did in his cave.

He did so then and had only just settled into the restive state that he found particularly conducive to isolating one sound from the others, when there arose a scream from behind. He turned to the sliding door, shut against the drone of power tools but not quite to the elevated pitch of a man’s voice raised in alarm. After a moment the door slid open and the contractor told him that his assistant had been badly hurt and needed to be taken to the hospital. He did not say that his assistant had been struck blind, though he had and had cut his leg because of it, all he said was that he would be back the following day and then hurried away to attend to his friend.

If, because of a sudden illumination, the blind man awoke one morning to find that he could see, he would most surely have hurried to the window closest to his bed to catch his first glimpse of the alleyway, though even if he had been endowed with the precious gift of sight, it was unlikely that he would have seen anything that disturbed him more than what he heard from his balcony during the week following the contractor's failure to return.

Lacking in sight, each of his colleagues had remarked at one time or another, it is well documented that one’s other senses become heightened. The blind man himself had always been skeptical about this, having only his own experience by which to judge, so that he knew nothing beyond the normal way that he heard and felt and tasted and smelled. Although, as to the latter, he had to admit that if his sense of smell wasn’t necessarily greater than that of a sighted person’s, it was certainly different, the only way he could explain why it was he always felt only comfort and warmth when confronted by the smell from the old woman and her cats.

Now, listening to the calamity descending upon the city, the blind man became certain that his friends were right, that his other senses had become finely tuned as a result from his blindness, so finely tuned in fact that they had formed another sense, a sixth sense, though he resisted calling it that, the term having too many connections with a supernatural world in which he most steadfastly did not believe. Let’s call it then a Gestalt sense, a coming together to form something greater than the whole, and within this Gestalt he saw nothing short of the end of civilization. A startling development for certain but, given the state of the world immediately preceding the epidemic, one that was not altogether unanticipated excepting, of course, the exact nature of its cause. Having lived almost his entire life without the benefit of sight, the idea that something as intrinsic to his being as blindness would cause a total collapse had never occurred to him and, if it had, he would more than likely have laughed at the notion, like a child laughs when a man falls down the stairs, not realizing that it is a far more serious matter than cartoons had led him to believe.

The blind man first began to recognize the severity of the fall, that is the broken bones and contusions resulting from such a rapid descent down steps likely to be as hard as rocks and sharper too, during the course of a day he came to call The Day Of Sirens. On the morning of this particular day, it was as if someone had thrown a switch that activated every siren and car alarm and klaxon in the city. In between breakfast and lunch, this frenetic bleating was at first merely unsettling, then rather annoying between lunch and dinner, and finally deeply disquieting while he lay in bed listening as the sirens and alarms and finally the klaxons trickled away, leaving the city, for the first time in his memory, entirely without any sounds whatsoever.

Unable to sleep and growing increasingly concerned about the state of affairs outside his apartment, the blind man slipped out of bed and filled his bathtub with water. He then filled the bathroom sink and set about the task of locating every container in his apartment that he could use as a receptacle. These he lined up on the floor. There were seventeen of varying sizes and he chose the largest, a bottle, it just so happened, for the water he had delivered to his home once a week. He carried it to the kitchen sink where there was a hose long enough to reach the floor but, when he turned on the tap, nothing came out except a dribble.

On the fourth morning after The Day Of Sirens the blind man stopped sitting on his balcony and listening for clues as to what was happening outside of his apartment. By then it was clear that things were not going well and that, in fact, they were so bad that the end of the city was audibly at hand, even if a few of its citizens hadn’t quite accepted that this was to be its fate. How else to explain why voices still reached him, calling for help or crying or venting their anger at the injustice of their condition?

Once he heard a woman praying as she walked past, only to have her prayers answered by a gruff voice warning her to Be quiet, or else. When that didn’t have the desired effect, the “or else” came by way of a soft thud like a piece of wood or a baseball bat hitting an unripe melon, followed by a series of similar thuds mixed with the odd rap of a piece of wood sounding more like a baseball bat with every swing as it struck the asphalt lining the alley. The gruff voice then proclaimed an end to the matter by asking the woman who had been praying what she thought of her god now. The woman did not answer, she was dead, the blind man knew that as certainly as if he had seen her body laid out, blood pooling under her skull, deflated, he imagined, like a water balloon which had been filled with red dye and dropped from the building’s roof.

Say to any man trapped alone in a room for a week, You’re free, open the door, give him a push and tell him, It is your world now, do with it what you wish, and that man may still not desire to leave. Such was the case with our blind man. An educated person, who coveted his intelligence above all else, he knew of many sayings which fit his current predicament but none more apt than the one we have all heard about a one-eyed man in the country of the blind. While not true, given the most literal of interpretations, he still felt it applied to him if only because his Gestalt sense was almost like an eye.

A less principled man might have given into the urge to test this old adage, letting it lead him in all sorts of directions a man with the proper combination of intellect and a lack of principles might easily be able to imagine. As it was, the blind man did not leave his apartment, afraid as much of what was out there as of what he might do if a suitable opportunity arose for proclaiming himself king. Trapped through his own devices or, more precisely, through his lack thereof, the blind man used up his store of hours the same way he often did when there was gap between one assignment and the next.

After a breakfast of two hard-boiled eggs, he worked at his manual typewriter on a book that had been popular when he was young and which he considered his personal favourite but, for whatever reason, because of the market or a general lack of interest on the part of the blind, had never been translated into Braille. The power had gone out at the same time as the water had ceased to flow from his taps and, without electricity, he was forced to listen to a recording of the book using the portable cassette player he kept in his desk drawer.

_edited_edited.jpg)

Though he much preferred hearing the voice of the long-dead actor amplified by the speakers on his stereo, through which it resonated with a deeply booming solemnity more suitable to its content, he was quick to concede that making do with the means at hand was better than the alternative. Lost, then, in this bridging of two worlds as disparate as English and Portuguese or, mimicking the more descriptive language used by his preferred authors, as the sand in a desert and that washed up on a beach, the morning took care of itself, which is to say that it went quickly and left the blind man feeling both exhausted and exhilarated.

At noon, he ate a light lunch and afterwards took a short nap. His routine broke down somewhat when he awoke as he was in the habit of going for a walk to shake the cobwebs out of his head and to prepare his appetite for dinner. He compensated by circling the island of furniture in the middle of his apartment for a half-hour or so. He then sat on his couch for a few minutes as he would have on a park bench, before circling the apartment for another half-hour in imitation of his return home.

Leaving aside the dust that takes advantage of the wind generated by the operation of any sort of electrical device so that it creates a light coating over everything not covered, power tools being particularly opportunistic as they not only turn up the dust but produce it as well, and the general clutter that results from the upheaval that an apartment undergoes in the process of a renovation, any untidiness in the single room to which his living quarters had been reduced was only what one could expect from a bachelor whose cleaning service had failed to arrive on the previous Wednesday.

The blind man considered himself a neat person, in appearance and tastes, and, before the calamity had struck, he’d had the foresight to ask that the contractor set any item brought into the apartment against the wall beside the front hallway and also that he be given an inventory of everything that was put there so that he could avoid any possible confusion if, for example, he tripped and fell over something accidentally left in the middle of the floor. My assistant is very conscientious, the contractor assured him. Yes, but accidents do happen. He will be careful. Please humour me. Of course.

So it was that the blind man knew when he tripped and fell in the course of one of his afternoon walks, that it was as the result of a tool called a sawzall, the same tool that the contractor’s assistant had cut himself with and that ever since had sat discarded on the floor. Beneath the blade, sharp to the touch, not so much like a serrated knife as a piece of coral, there was a pool of blood that the blind man knew nothing of, the sticky resin having dried into a hard puddle no more noticeable than the brown water marks souring his ceiling. The blind man collected the offending tool from the floor and set it against the wall. Then, because his knee hurt and he didn’t feel like continuing his afternoon walk, he spent the remaining hours before dinner probing his hands over the irregular piles of materials and boxes until he had acquired enough knowledge of each item’s form so that he could also make a reasonable guess as to its function.

Two days later the blind man said to himself, I’d like to know what mother would say if she could see me now. What he meant by this was that he hoped she would be suitably impressed, a sentiment that was out of touch with the person he knew his mother to be, someone who would, in all likelihood, hold an altogether different opinion of the task he was engaged in, which was finishing the work left undone by the contractor and his assistant. She would, now that he thought more thoroughly on the matter, most likely scold him for putting himself unnecessarily at risk. What if you hurt yourself, she would say, There are no doctors to look after you, Any wound you acquire will become infected, You will die from vanity, Is that what you want? Yes mother, he would answer her, that is precisely what I want. And what does it matter anyway, it is not as if you could tell the difference. That is where you are wrong, mother, While it may be true that I cannot see the difference between, say, an exposed crack separating sheets of drywall lacking the concealment of plaster, it is also true that I have never before seen such a crack so completely, for in the time since the contractor failed to return, my fingers have seen every inch of my apartment, and they have felt it lacking in even the most basic qualities required of the place in which I have chosen to live.

This conversation, starting in his thoughts, shortly sprang forth from his mouth. He was sanding the plaster he himself had lathered into the cracks, his fingers a better judge of its smoothness than any working pair of eyes. The words lingered in the empty room as words often do when they are the only thing between a person and a feeling of complete and utter loneliness. Unnerved by how foreign his voice had become in the absence of any others, he set down the sanding block and walked to the sliding door. The air that had settled over the balcony reeked of rot and feces. The blind man held his breath against the stench and counted upwards from one to keep himself from imagining where such a smell could be coming from. When his count reached twenty and he hadn’t heard anything beyond a frantic scuttling, perhaps that of a rat caught in the garbage dumpster he shared with the convenience store below, he closed the sliding door and returned to work.

The next day, while still in bed, the blind man spoke aloud a second time, telling himself something that he already knew but which he felt warranted breaking the silence he’d imposed since his outburst the day before, You are almost out of food, Yes, One piece of bread left, a little bit of honey, I know, now will you stop pestering me about it.

Because it is in man’s nature to forget about the sufferings of others until reminded of them by his own, it was at that moment that the old woman who lived across the hall returned to the blind man’s thoughts. She’s likely to have less food then yourself, She is probably starving by now, She is dead, Why do you say that, Because you know it to be true. Unsettled by the sudden turn in the conversation, the blind man pushed his covers aside and drew himself out of bed.

There was a fine dusting of powder on the hardwood floor, the result of the sanding he had done in preparation for the first coat of paint that he hoped to apply tomorrow, and he made foot-shaped tracks to the hallway where they suddenly vanished as if they had been made by a ghost. The blind man knew nothing of the tracks except a vague sense that there was something different about the floor or the soles of his feet, in his drowsiness he couldn’t discern which, so that it or they felt slippery, like he was walking on ice. The feeling shortly gave way to the coarse weave of the welcome mat in front of his door and he paused there, his outstretched hand stalled, refusing all of a sudden to obey its master’s command. The blind man rallied it with gentle admonition and, after a moment’s indecision, his hand responded by flipping the latch and pulling open the door.

When he unlocked the corresponding door across the hall and swung it inwards, the rankness of the odour that confronted him was such that he found it hard to comprehend. It was like a wall separating him from the apartment beyond. He stood on the threshold, unable to push past it until he heard the mewling of a cat, then he stepped inside and closed the door to prevent the animal from escaping. Still, he wasn’t able to progress beyond where he now stood, his hand over his face, his shallow breaths taken through his mouth. And maybe he would be standing there yet, unable to reconcile the stench here with the one which, when he confronted it in the hall, had always told him he was nearing home and happy for it, had it not been for the continued mewling of the cat.

That it was in distress there was no doubt but what its particular affliction was we shall have to leave to our imagination, as it was left to the blind man’s. Possibly it was on the point of starvation, which the blind man could have easily discerned by running his hand over its ribs, protruding from its sides like the frame of a boat before the hull was attached, or possibly it had taken refuge in dementia, the only solace it had against recalling the things it had done to the old woman and to its brothers and sisters.

As the cat approached, the blind man became certain in the wretched sound of its suffering that it would be a mistake to treat it as he had during his previous visits, which is to say loving and kind, and he groped for the cane he knew to be propped in the corner along with an umbrella. He clenched the straight end and raised the curved part above his head but the cat went quiet the very moment the blind man suspected that it had come within his range.

The coldness of the hardwood floor seeped into the soles of his feet and his mind wandered back to the three pairs of shoes neatly arranged in his front hall, a thought that was interrupted and reinforced at the same time by the sharp prick of claws raking over his bare toes. He kicked out at his attacker, striking it in the head. The cat screeched and fled, and the blind man waited until its distant mewling told him it was hiding, likely under the couch so that it could watch him as he made his way through the living room. Possibly it hoped that the blind man would trip on the bodies of one of its kind, a half-dozen of which were spread over the floor at intervals, so that it might pounce.

If this was indeed the cat’s wish, it would be disappointed. The blind man did not trip, nor even stumble. He did, however, put his foot down into something soft and warm and unmistakably dead and the feel of it squishing between his toes opened his stomach as surely as if it had been a knife, causing him to suddenly vomit onto the floor. To avoid future missteps, he then used the cane to probe the carpet ahead, like a blind man walking with a stick, a device he’d never used before the calamity struck, preferring to see the world with his hands and through the soles of his shoes and with his ears and nose and mouth.

Several times he used the cane to push an obstruction from his path and once he found that the object in his way could not be moved. He tried not to think of it as the old woman, preferring to think of it as a piece of furniture that he couldn’t merely step over and instead had to inch around. The kitchen lay beyond this ottoman or that toppled shelf and the blind man fought the urge to sit on one of the chairs at the table to rest for a moment, feeling so tired that it seemed like he had just walked across town and not through the living room of a small apartment.

The cupboards over the sink were lined with dozens of small cans and nothing else resembling food. He felt through all of them, then took one out and searched through the drawers until he found an opener. He applied this to the can and the aroma of minced meat, bearing a faint trace of fish, made his stomach twist. He fought back the urge to be sick again and set the opened can on the floor by the kitchen door. After a brief moment, the cat rubbed its face against his knuckles with a gentle nudge that suggested that it had already forgotten the kick he delivered to it only a few minutes before. He stroked the cat’s fur, not caring that it was matted and hard nor that the cat didn’t respond to his touch, consumed as it was by the contents of the can. When the cat was done it slipped from under his caress and disappeared once again into the apartment. He loaded the rest of the tins into the four plastic bags he’d found wadded into a ball under the sink and returned through the living room, no longer needing the cane to find his way, such was his memory, honed from a lifetime of journeys home into something that might even be called a seventh sense.

The dry smell of plaster dust in his apartment and the taste of it on his tongue were as good as any drink of water. He stood at the end of his hallway, letting it wash away the smell of the dead woman and her cats, and peered into his living room, imagining the naked blotches of plaster and the lightening, brightening yellow on the walls, the image appearing so clearly in his mind that he was helpless but to think, It’s almost as if I can see them.

Hope made him quickly shut his eyes. The amber and white were still there.

_edited.jpg)

Trees in Ice

by Rebecca Kramer

Oh rarest day of winter blue

Through weeks of grey I longed for you

And waited for my face made new

When tickled by loving sun

Oh rarest room near waterfall

In icy bloom this concert hall

Had audience of trees receive

A golden shortbread spray

Oh rarest thought I nowhere find

In Church of God or State of Mind

That doesn’t make the earth a tomb

And glorify the sky

Or call the senses ‘Burning Coals’

That when indulged will scorch the soul

And drive the puffed-up spirit back

Into the sin-flesh hole

For after all the spirit rules

The flesh is weak and we are fools

Until enlightened we can prove

Our victory over flesh

And victory is cruelty driven

Where loveless hierarchy is taught

Where mind over matter despises the latter

And spirit over flesh just lets the flesh rot

The saddest thoughts throughout the world

From oldest books through time are hurled

That sex is evil…flesh is female

She defiles him who is pure

She is wild like the wild lands

Like the creatures hunted hard

Near extinction trapped in deserts

Rich in nutrients underground

She is waiting…longing…hoping

For a Sunday such as this

Where the fullness of her beauty

Like the ice trees others kiss

Oh rarest thoughts I’ve hardly found

But live them in my underground

Where body spirit earth and sky

Have left hierarchy far behind

Where senses do inform the mind

And dreams the tired spirit find

And trees in ice great logic wind

I’m finally free to hear them

Did Jesus smile?

by Rebecca Kramer

_edited.jpg)

After the death of my mother, I was accepted into seminary at McMaster University in Hamilton in 2002 to become a pastor.

I was only enrolled for the first three weeks since I had no tuition to continue. But I also couldn’t resolve an internal conflict: I had been raised in the church to believe that women are forbidden to lead and yet I felt a leader by nature. Until this conflict was resolved, I knew that taking on the role of a pastor was unwise and unfair to a congregation. Therefore, as my time would be short there, I took in as much as I could. Around the same time, I also returned to my home church in Hamilton. Little did I know that my life was about to take a wild spin at one particular Wednesday night Bible study.

My story begins with a positive discovery, years earlier. At an arts exhibition in Vancouver, I had come across Leonardo da Vinci's Smiling Jesus. It is an essential painting, a copy of which I hung on the wall in my lounge.

Now during that evening's Bible Study at the church, the topic of discussion was, “How can we get more people into the church?” Thinking of Leonardo’s Smiling Jesus, I said innocently, “Why don’t you smile more at the people who do enter the church?”

My comment unleashed the full fury of all three pastors there at once. The 300-pound head pastor even pounced to his feet, loomed over me and yelled, “You are to come under my authority at once.” Even my father responded negatively by abandoning me. He looked at me with scorn, got up and slowly walked away. In shock I watched his back become smaller and smaller and then disappear; my spirit dwindled inside of me. I asked him in my mind, “Dad, where is your courage to defend your own daughter? Am I not worthy of support?”

The next day, I spoke with another one of the pastors on the front steps of the church. I said, “Jesus smiled.” He said, “No, he did not.” Very astonished I asked him, “Why?” And then he made the most ignorant comment I have ever heard from any pastor. He answered, “Show me the verse!”

My eyebrows went through the roof. “Show you the verse?” I asked back. “You mean to tell me that you actually have to see a verse written in the Bible to consider whether or not Jesus smiled? You honestly believe that thousands of people followed a miserable and morose man all over the countryside?" I pressed, “Do you even warmly greet your wife and daughter when you come home?”

The pastor had to admit, “No.”

Years later I ran into him. He smiled wryly as he stated, “My marriage has ended.”

That day, in complete shock, I walked straight into the seminary to discuss the possibility that ‘Jesus smiled’ with the professors in their offices. How odd and most peculiar I found them to be; they all just stared blankly at me, as blankly as the pastor had. I had hoped professors would be more liberally minded than these Baptist pastors: especially about the basic concept of whether or not Jesus smiled. But I assumed wrongly.

The very next day, the dreaded phone call came from the head pastor of my home church. He proclaimed threateningly, “Rebecca, you are now excommunicated. If you ever set foot on our church property again, we will call the police and have you arrested.” Bewildered, I walked to the seminary hoping to find solace there. But the head pastor had already contacted the university to taint me as black as soot.

Later that autumn, the result of my excommunication caused the people in my home church to abandon me completely at a critical time when I would have needed them the most.

_edited.jpg)

Sunday after Sunday, the church families invited my father to dinner to help him grieve the loss of his wife; but no one cared enough to invite me to help me grieve the loss of my mother. I was isolated in the world, so alone and ostracized that the weight of it still haunts me. Only one woman took me out for coffee. She told me, “I love the lilt in your voice when you sing.”

Right after my excommunication, the moment I entered the school, the large dean of the seminary ran at me just as ballistic as the senior pastor had. He stormed, “Rebecca, you are expelled from this seminary. Leave at once. Go. Get out of here, right now, and never come back!” And, just like that, I had no church and no school to go to: all within one hour. As I walked through the streets and sat down on a park bench, I began to ponder what I had just learned. I needed to salvage something; anything positive.

Three memories warmed my heart. For orientation, all the new seminary students had gone on a retreat. The singing was breathtaking. One hundred people, all headed for leading group singing as pastors, where raising the roof together. I doubted I would ever hear anything like it again on this side of heaven.

Next, I had taken a class in Hebrew; the language of the Old Testament. I learned the letters of the Hebrew alphabet and found myself able to very slowly read an ancient language.

Lastly, I attended a class led by a rather interesting female professor.

“I'll try anything once, so I can understand what people are going through.” I'd said. The professor was astounded and asked, “You'd just jump into their frying pan?” I'd nodded.

The professor urged, “Then, Rebecca, you don’t need to be sitting here in this class. You need to be out there!"

I thanked her later in her office. Ironically, this female professor had given me the 'soft boot' with a gentle blessing while the dean of the school had given me the 'hard boot' with a blazing curse. Either way, I was booted out of that seminary. I was obviously not meant to be a typical pastor, but perhaps I was meant to be a pastor of another variety; a sort of missionary maybe?

Later, I was to remind myself that all was not lost: that the powerful nuggets of truth I had received during my preciously short time in seminary at McMaster University would never have come across my path any other way.

I'd learned, first and foremost, that the essence of a pastor is to be a good shepherd. But it dawned on me that, rather than being a typical pastor who locks a church building with the alarm set at the end of a long day of working on their sermon in the church study, there was the option of becoming a shepherd in the style of King David when he was a boy. He proved it could be done; to take care of his sheep without a fence. I intended to do the same.

A pastor is a shepherd who cares for every one of her sheep and attends to them individually, lets them roam, eat and play freely. The shepherd is always gracious to the roamers; she knows them well and is aware of their motives for leaving. Therefore, she lets them go with her blessing. They may have gotten indigestion from the grass in a specific pasture; they may have borne the brunt of a bully and are looking for a kinder flock; or, frankly, they may just be bored of their shepherd. Most sheep stay close; some are curious; and maybe one is in severe crisis. That lone sheep has lost its bearings.

“Where is my true North?” it cries, trying to find its way in the wilderness. The shepherd rescues the lost sheep and celebrates its return to the flock. And that is what a good shepherd does: she tames gently, she searches, and she welcomes the lost back into the flock with open arms.

I realized, as that warm September afternoon was wearing on, that anyone in that church or the seminary could easily dial 911 and bring down the curtain on me even further. Thus I feared walking the streets to return home. I was worried that, besides the pastors and professors, the ordinary people in Dundas posed a threat as well. Let me explain.

At an intersection, I was running across the street to avoid being noticed by the police. A driver saw me running, got the impression I was trying to throw myself into traffic to end my life and called the authorities. (Later in the psych ward, I would ask the psychiatrist, “Why am I locked up here?” and he answered, “You threw yourself into traffic to commit suicide. You are a danger to yourself. I therefore have legal grounds to detain you.”)

_edited.jpg)

I managed to clear the intersection successfully, but felt I was ready to collapse with exhaustion. So I asked a woman who was tending to her flowerbed to call a taxi for me. My distress must have appeared suspicious for she gave me up to the police as well. The cruiser arrived and a pair of brutes handcuffed me, literally dragging me roughly in my sandaled feet down the gravel driveway, which left them bruised and bleeding. Mercilessly, they escorted me handcuffed into my 20th psych ward hospitalization at McMaster Hospital.

Ironically, the seminary building was barely 100 feet from the psych ward. Chucked out from assuming a respectful position in society by becoming a pastor, I was chucked into the hot frying pan, with no rights, no future at all, but to grovel with the least of the least of them, all because I liked to smile at others; strangers, friends, and family alike. To the world I want to say, “Do not come to Canada expecting to be welcomed warmly. The more caring you are, the worse they treat you. Stay clear of this deceptive country.”

Stunned into silence, in thin cotton PJs, I walked the halls aimlessly for two days, but then I had an idea. During this particular hospitalization, I decided that I had something to prove, that, though those who have mental illnesses may have minds that operate in unusual ways, they are also capable of strong ethical and moral values. They deserve an opportunity to voice them. I sought to prove this to myself, to the other patients in the ward and to the psych staff. Therefore I asked all of my fellow patients a specific question. Their eyes shone; I will never forget their enthusiastic responses.

_edited.jpg)

I asked them, “From your heart and your mind, teach me something that is true, for you.” And as an example I quoted Jesus: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you." At that hospital, I was given permission to use the computer room. What I was up to seemed harmless enough to the nurses. I typed out all the patients’ sayings and taped them onto two doors in the ward. Periodically, the nurses would rip down the pages and throw them away. Then I would just start all over again.

At this time, I must mention that I witnessed a deplorable event that took place during my month in that ward. One woman tried to commit suicide in an isolation room. To punish her for her crime, the psych nurses devised a perfectly gruesome medieval torture. They were sick motherfuckers. The psych nurses placed her in a room with the door wide open; they restrained her ankles and wrists spread-eagled onto a bed; they arranged her legs spread wide apart and facing out towards the hallway, with the door ajar, to sexually humiliate her; they put a catheter into her to collect her urine; and they fed her intravenously.

They left her there like that for an entire week. All she could do was moan and groan and yell and whimper in bitter agony, hour after hour, day after day: Torture untold in Canada in 2002? No, it can’t be. Oh yes, it can be. Accept it as fact. Unless torture in psych wards becomes common knowledge, it will only continue to fester in this country. That’s why I am telling you this! God damn it! I have seen enough. I have seen it all. I refuse to be silent any longer. I could care less if I bring shame upon myself for admitting I have a mental illness. Big deal. The treatment of mental illness needs to be exposed by someone. It may as well be me.

All of us other patients, who had to listen to this all week long, felt heartbroken. We talked amongst ourselves about how cruel these nurses truly were. The most obvious comment we all agreed on was this: “How, by tying her up like this for an entire week as a punishment for attempting suicide, is she now supposed to restore her will to live? Wouldn’t she, after this traumatizing experience, want to end her life all the more?”

At one point, I walked by her room and said, “Hi.” The woman looked up and answered, “Hi, Rebecca.” Immediately a nurse threatened, “Rebecca, if you talk to her one more time, you will be locked up in the seclusion room.” The woman on the bed said, “But she is my friend.”

I winked at her while the nurse was looking the other way. Then, every time I passed her room, I looked to make sure the coast was clear; and we smiled at each other and winked in silence. We had outwitted the miserable staff. At that seminary and in that church, I had been a candle in two well-lit rooms, but during this hospitalization, I was a candle lit in the darkest room of our society. Fate had brought me to this woman who had called me her friend. Was I her smiling Jesus or was this woman actually my smiling Jesus? Perhaps both?

Looking back at the events that pivoted my return to Ontario from Vancouver Island, beginning with my rape, my mother’s death, my excommunication to my expulsion, my betrayal and then to my confinement under lock and key for yet another month of my life; this gigantic crash of dominoes had all happened within a 6-month period; from May to November in that same year. But, despite these setbacks, I knew where I stood.

If you were to ask, “Rebecca, from your heart and mind, tell us something that is true to you?” I would warmly answer to all, “Jesus smiled.”

I take heart. Leonardo da Vinci was excommunicated too! Ha ha! Gag me!

Frosted Creek, Rebecca Kramer

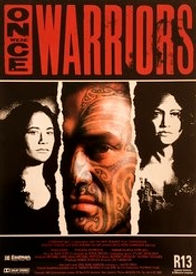

Once Were Warriors

1994, New Zealand, R, Drama,

Director: Lee Tamahori

Starring: Rena Owen, Temuera Morrison

Screenshots

with Tanja

The rain hadn't taken a break for at least a week, the City wrapped in perpetual haze. Fortunately, escape from the dreary patter happened to be just a short walk away.

On the other side of our West End neighborhood sat the Capitol 6 Theater, a welcome refuge for any cinephile, offering entertainment that makes us hark back nostalgically to a time when the allure of an evening at the movies still induced a modicum of excitement.

This particular venue in the heart of downtown Vancouver's entertainment district originated back to 1921, then known as the Capitol, and, with 2500 seats to a single screen, was massive for its era and fittingly ushered in the Roaring Twenties. During the 70's it was converted to a six-screen, three level multiplex, at the time the only movie house featuring more than three screens in the Lower Mainland. It still had retained some of its former glory in the 90's when we came to know it intimately, with large modern chandeliers descending from high ceilings, sweeping staircases and convenient nooks and crannies to temporarily avoid managerial supervision - so pleasantly unlike the noisy, uniform contraptions we endure today.

As the official Western Canada flagship of the now-defunct Famous Players theater chain, it was a celebrity stalker's dream. With movie previews and star-spangled openings an almost weekly routine, spotting who's who in show biz became a competitive sport. My personal favourites include selling a ticket to Patrick Stewart one slow afternoon that left my heart pounding (damn that voice!) and a short but sweet conversation with Roger Moore's son whose dad gave me a friendly wave on their way out.

Harrison Ford, Richard Gere, Jean-Claude Van Damme, Cindy Crawford, Leroy from Fame, that guy from Jump Street, Danny Devito, Marilyn Manson, David Duchovny, Winona Rider, Ray Dawn Chong, Jonathan Frakes . . . to name just a few, and the odd one providing great anecdotal material we fondly recount to this day. (Remember Van Damme having a meltdown over a bag of Nacho chips and Leroy singing show tunes and dancing his way up the stairs?)

Friends were made, hearts were broken, staff came and went, drunk midnight screenings, living on popcorn, overcooked hot dogs and cheese dip, sneaking in friends, checking the seats for change to help pay for groceries or a beer after work, slow, boring shifts, blockbusters with long line-ups around the block, smokes shared in the loading dock, and garbage, ever-more garbage.

John and I had been working together for about two years when things started to click between us, and it was during the early days of courtship that we had time to kill one rainy afternoon and headed down the street to our theater, intrigued by a new poster on the marquee (see above) and its corresponding movie review in The Georgia Straight.

After enjoying The Piano, a New Zealand co-production, the year previous, we were certainly expecting intriguing, possibly controversial, fare, but nothing had prepared us for the gripping and violent journey ahead - not even the intensely worded review which proved a pale substitute for the imagined reality of passionate film making.

From the moment the lights dimmed, the world around us disappeared completely as we were pulled into Once Were Warriors, a story too up-close and personal to spring from the creative mind. These weren't simply fictional characters acting out a script, they appeared real, their lives disturbingly exposed on film with the audience acting as helpless, even complicit, bystanders to their heartrending drama. Its strong undercurrent of violence, ever threatening to breach the screen, held us suspended in animation as urban Maori strongman Jake 'the Muss' (Temuera Morrison) transforms from charming thug to pair of raging fists in the unguarded blink of a perceived slight, heedless of his target's size or gender. His sober gestures of remorse instill a feeling of conflicted dread in the viewer, the underlying menace of his explosive temper ever-threatening to break through the thin layer of his geniality. As the violence slowly and brutally sets to destroying his family, blame cast self-righteously at all but himself right to the bitter end, we see the force of his aggression turn into powerless rage as his wife Beth (Rena Owen) reclaims her own 'inner warrior' and resolves, by reconnecting with her Maori kin and heritage, to save herself and her children.

As the lights came on and the credits rolled to the raucous sound of guitar strings, we reluctantly returned to the world around us. I was left with a strange sensation that should have been unpleasant after such aggression and grief, yet the more fitting description might be 'cleansed' - emotionally exhausted while at the same time light but grounded, proud and, yes, strong. True Movie Magic. As we repeated the viewing twice over the next two decades, its dramatic impact barely diminished though, admittedly, the big screen experience in Dolby Digital certainly enhanced its powerful execution.

Many were the times I genuinely felt for Jake, the aggressor, a man convinced of his own generosity and good nature, yet deeply plagued by an inferior tribal status and tough upbringing with nothing to fall back on but his misguided pride in the warrior he desperately needs to be. He, himself, is the prime victim in this harrowing though hopeful tale of strength lost in adversity and found in community, which he ever so sorely lacks. His uncontrollable temper and anger mercilessly conspire to defeat even his best intentions each step along the way with only moments of illusive hope that he might yet escape the birthright of brutality passed down to him through generations. It drew striking parallels to the legacy of violence and addiction Indigenous peoples on our continents, North and South, have been left to struggle with after their near extinction eroded cultural, tribal and family ties.

And if we, as a society, could take responsibility for our past by, at the very least, actively encouraging and supporting our own First Nations filmmakers to embark on equivalent ventures, we wouldn't have to reach halfway across the globe to import the truth.

Mackaycartoons.net

Theo Moudakis, thestar.com

In Memory

Wendy Campbell

A Story Seldom Told...

by John Jantunen

_edited.jpg)

In June of 2020, I received an email from Jack David, my publisher, asking me to look over the proposed jacket copy for my forthcoming novel, Savage Gerry. By way of a potential bio he himself had written, “John Jantunen has lived in almost every region of the country and is constantly shocked and dismayed that the Canada he has experienced is so rarely represented in our nation’s literature.”

While I’ve often made comments testifying to the same, I suspect that he’d written it with tongue firmly in cheek and that his real agenda was simply to spur me to provide him with something more substantial than the bio I’d previously submitted, the sum total of which read, “John Jantunen lives in North Bay". Regardless of his intent, the email enlivened my mood in no small way, serving as an affirmation that Jack, in the least, seemed to have a firm grasp of what motivates me as a writer.

For it has indeed been the cross-country odysseys I have taken both alone and with Tanja as a fellow adventurer which have mainly informed my fictions, or rather it is the people I, and we, have met who shared their stories, and sometimes their lives, with us. And it’s equally true that many of those stories are underrepresented, or not represented at all, in our nation’s literature.

I wrote at some length about the myriad of reasons why this might be so in Cannery Row’s first issue so won’t belabour the point here, except to say that I’ve been somewhat reluctant to write about a few of them myself. That it’s generally the most compelling of the stories I’ve heard which are also the ones most difficult to commit to the page is a vexing problem for any writer and especially one who endeavours to present a more nuanced portrayal in his fictions of a country than is ever likely to, say, be short-listed for a Giller. And of all the stories I’ve heard, none is more compelling than the one Wendy Campbell told me about her involvement in The Antigonish Race Riots.

Wendy ran the African Heritage and Friendship Centre at the Chedabucto Education Centre in Guysborough, Nova Scotia, while I was a co-facilitator for the Rural Youth Education Project, a pilot program run out of the Antigonish Women’s Resource Centre which delivered an in-class curriculum on healthy relationships to students in grades seven through twelve. My co-facilitator, Krista, lived in Antigonish but had family in Guysborough and often spent her lunch hour visiting with either her parents or her sister. I bagged my lunch and, since the Friendship Centre was easily the nicest room in the entire school, I naturally gravitated towards it. The first time I came in, I was barely through the door when Wendy, sitting behind her desk, asked me rather curtly, “Is there something I can help you with?”

“Just looking for a place to eat my lunch,” I told her, holding up my bag.

Wendy gave me a rather dubious look but told me I was welcome to eat at one of the tables nonetheless. I’d end up spending most of my lunch hours there and shortly learned that, contrary to my first impression, Wendy was about as welcoming, and gregarious, a person as I’d ever met. She was also a storykeeper for the county’s two Black communities. Listening to her recount the oral histories of Lincolnville and Sunnyville over lunch quickly became the highlight of my day and, after a few short weeks, we’d established enough of a rapport that one afternoon I felt comfortable remarking upon my impression of her the first time I came in.

“I was just surprised, is all,” she replied. “White people never come in here. I thought you must have been lost.”

I’d already born witness to the de facto segregation which existed in Guysborough, having worked for a year and a half at The Guysborough Legion, which was frequented mainly by residents from Lincolnville and Sunnyville (Tanja and I were living in a house in Guysborough Intervale and during my tenure, for example, I’d asked Ronnie, a regular, over for a beer. He'd responded by asking, “You live up in the Interval?” I told him I did and he said, “Black folks ain’t allowed up in the Interval.” “What?” I’d asked, suitably aghast. “Someone sees my car parked in your driveway, it’ll mean a brick through my window, or worse.”)

So it made sense to me that Wendy figured I’d wandered in there by mistake though, I’d find out, that wasn’t exactly the truth either. The truth was, she’d confide to me some months later, she’d known exactly who I was, or rather who I worked for. She then went on to relate that when the Antigonish Women’s Centre first opened, her and a group of women from Lincolnville had gone up there to seek help in combating the domestic abuse that was rife within their community (a similar state of affairs which is seemingly endemic throughout rural Nova Scotia, in Black, Indigenous and white communities alike).

“But they only care about white women and their problems,” she told me, after recounting how their appeals had been met with stony silence. “They don’t give a damn about us and it was because you worked for them that I was a little sharp when you first came in.”

Our relationship had entered into a new phase by then, that of co-conspirators, which no doubt played a significant role in why she’d, rather suddenly, felt the urge to be so forthcoming about her experience with my employers. The conspiracy we were engaged in wasn’t much of one as conspiracies go, and probably didn’t even really qualify as a conspiracy at all since our activities were sanctioned, even encouraged, by the school’s principal, though by necessity we had to fly under my boss’s radar (and when she found out what we were up to, she sure treated it like a conspiracy so maybe it was one after all).

A central feature of The Rural Youth Education Project was that it enlisted a team of ten grade twelve facilitators, five of whom were female students and five male and whose central role was to help model healthy relationships for their fellow classmates through a variety of exercises.

The present team had been chosen the previous year and, while Black students comprised roughly twenty percent of the school’s population, our team was exclusively composed of white students. This 'regrettable' lack of diversity, I was informed by my boss, was simply a matter of bad timing which stemmed from the entire Black student body having staged a walkout the previous spring in protest against the school’s 'unfair' disciplinary practices.

My boss was short on details but Wendy quickly volunteered to fill me in. She explained that a female Black student had gone into the teacher’s lounge, which had a window overlooking the gym, so she could wave to her sister playing below to tell her that she was leaving. She was 'apprehended' by a teacher who accused her of stealing and was subsequently suspended for two weeks, although no evidence of a theft was ever found. A short while later, two white male students really did steal a couple of wooden masks from The Friendship Centre and proceeded to don them on the bus ride home while hurling racial slurs at their darker-skinned classmates. They were only suspended for two days and so the entire Black student body walked out in protest. It just so happened that this occurred during the same week that our program was to select its student facilitators, which is why my boss could attribute the lack of diversity in our team to 'bad timing'.

Wendy was of an entirely different mind. Even though her own negative experience had tainted her view of the Women’s Centre, she was one of our program’s staunchest advocates, both within the school community and the greater community at large. She believed, as I did then and still do now, that real change could never happen without first finding a way to have those hard conversations through which all parties could speak openly and honestly about their lived experiences. This was also a central tenet of our program and the Women’s Centre’s refusal to make accommodations for the school’s Black students had become just another example of the same sort of 'lip service' she’d heard being paid to her community by white people in positions of authority throughout most of her life.

When two of our male student facilitators dropped out of the program after only a couple of months, Wendy seized on the opportunity to correct at least that one wrong. She approached Krista and myself with a plan to hold a new series of interviews which would allow two Black students the chance to become a part of our team. Both Krista and myself had often discussed how we might accomplish the same thing and we eagerly agreed with her solution but when we broached the topic with our boss, we were told in no uncertain terms that such would not be possible and that we were to make do with the remaining eight facilitators.

Quite frankly I fully expected Wendy, upon hearing the news, to be mad as hell (a justifiable response in my mind) and was thus surprised when she instead responded rather matter-of-factly, “Then we’ll just have to do it without her.”

_edited.jpg)

I’d love nothing more than to report that I greeted her pronouncement with a similar resolve, but the truth of the matter was quite the opposite. Our sole income at the time was the $800 dollars a month plus mileage I received from the Women’s Centre along with whatever 'baby money' we received from the government for our then-newborn son, Anyk. Plus, I’d already got myself into some hot water with my boss a short time earlier for something I’d said during one of our student facilitator meetings.

The topic up for discussion that week had been how harmful words can be. It was an exercise intended to provide the young women in our group with an opportunity to have an open and honest discussion with their male counterparts about how being called certain derogatory names could itself be a form of trauma. When I told Wendy about our upcoming meeting, she’d suggested rather pointedly, “You should ask them what they think of the word ‘nigger’. I know, for a fact, most of their parents still use it.”